]

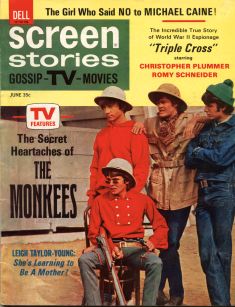

][originally appeared in June 1967 Screen Stories ]

]

The first interviewers who went out to meet them come back non-plussed. The Monkees would do all kind of daffy things on the spur of the moment. One interviewer found herself surrounded by the boys, who played cowboys and Indians around her, insisting she was a tree. Another interviewer, after meeting them, swallowed several aspirins and something stronger than aspirin and gasped, "I interviewed the Monkees, and thank God, I'm still alive." Another writer trying to sum them up described them as a "fearsome foursome of way out gag-howling, quip flipping, mop topped lunatics."

It is true that they can raise happy Cain when they feel like it but behind the surface joyousness there are secret heartaches in all their lives., In order to preserve what their publicists thought would be the proper "Monkee" image, the heartbreaks in their lives have been played down, in the hope that their audiences would swallow the story that the Monkees are a completely carefree lot.

That's far from the truth.

At 20 Davy Jones seems to be a happy-go-lucky Englishman. But there's another side to him. One day a newspaperman learned he had spent his life's savings on a $20,000 house for his father, an injured retired railroad worker in England.

"What about your mother? Is she still living?" the reporter asked. Davy shot an anguished look at the reporter, answered, "She died six years ago," and walked away.

That reporter had struck a raw nerve, one he might not have struck if he'd known more about Davy's background.

As a child Davy had been very poor. The thought of how hard his parents worked his a mere pittance bothered him; it also bothered him that he was very small for his age. Other kids his age were growing quickly. "They looked down on me from their superior height, and I felt like a nobody," he said in one of his rare moments of self-revelation.

At 16 he was four foot seven; he was always hungry. It seemed as if he could never eat enough or grow enough. It bothered him terribly. Then he learned that small boys like himself were wanted as jockeys. "I had visions of riding winners to the cheers of a crowd, and earning lots of money, so I quit school and became an apprentice at the race track. Deep down I still wanted to be on the stage, just as I always had, but I thought my size made that impossible."

Actually, Davy didn't win the fame and fortune he hoped for as a jockey. But a friend who was the owner of a stable learned of his theatrical ambitions and urged him to try out for a role in the play "Oliver," which was going to be presented in London. Never believing for a moment that he had a chance, he tried out and to his astonishment was chosen as the Artful Dodger. As he himself says, "I was like a drowning man who grasped a twig and found it was a lifeboat."

The role in "Oliver" led from London to the United States, where "Oliver" was a great Broadway success. Davy lived economically and saved as much money as he could. Now he could dream of increasing success on stage, and how he would make up to his parent for all the hardships they had endured for him.

And then one day, the bottom fell out of his world.

He got the news quite suddenly that his mother had died.

And then one day, the bottom fell out of his world.

He got the news quite suddenly that his mother had died.

A friend of his said, "His goal had been to save enough money to buy his parents a house in England that would be all paid for a house no one would ever be able to take away from them. Last year he gave his father the deed to the house.

"His father said, 'It's a fine place and a fine thing for a son to do. But it breaks my heart your mother isn't here to walk into the house with me.'"

Davy turned away so his father wouldn't see the mist in his eyes. That night in his own hotel room, Davy found himself crying. He was crying not only for his mother but also for his father. They had both lost the one person they loved most, and his dream of making up to his mother for all the hardships she had endured must forever go unfulfilled.

Mike Nesmith's secret heartbreak concerns his father. His mother and father were divorced when he was very young. Mike grew up, wishing he had a father who could be a pal to him; he secretly envied other boys who had fathers who loved at home with them.

The world of reality, in which he couldn't be with his father, was one he hated to accept. Unable to accept it willingly, he retreated at times into a world of fantasy.

He says, "I'd like to forget a boyhood of nameless torment and frights, which were all the more terrifying because they never happened. I never expected to grow up; that's why as a child I found it impossible to think about the future. I was sure I was going to die in the near future. I had heard that if a person doesn't have some reason for existence he shrivels up and dies. And what possible purpose could my life have, I wondered?"

The thought finally occurred to him that if he could solve

the riddle of his boyhood and find out why his father had left

his mother and himself, he might be able to find his own identity

and stop being a misfit. He told a friend, John London, his stand-in,

how he felt. John had a father in Civil Service, who tried to

locate Mike's father through the public records and succeeded.

John's father learned that Mike's father had retired from military

service and was living in New Orleans. Mike arranged to meet his

father, hoping that meeting could give him the key he was searching

for, that would give his life meaning. Apparently his parents'

divorce and the fact that he never knew what had caused it had

a traumatic effect on him.

Whatever happened at that meeting is something that Mike refuses to talk about. Some friends say that he was deeply touched, and hopes to see his father again. Others say that the meeting was a disappointment, that it did not ease his feeling of heartbreak. He did overcome whatever resentment he may have suffered from; he sent his father a color television set for Christmas.

But the real answer to his feeling of being lost in a world where he had been wandering like a stranger, has come through his work and his marriage and his little son. "I wanted vital reasons for living; I have them now, a wife and a son," he says. He hopes that his son will never feel as disoriented as he once felt, and he does everything he can to give his boy that precious feeling of emotional security he lacked as a child.

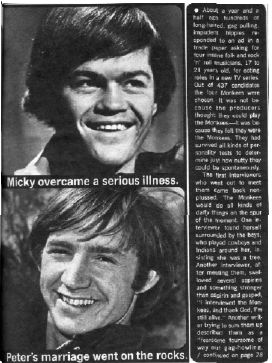

Mickey Dolenz' secret heartbreak came not through his parents, but through a girl. He was living in Los Angeles when he met her, and feeling very much alone, for his father had died and his mother had remarried. He fell in lover at about this time, but the girl didn't care for him as deeply as he did for her. Micky told a friend, "It was an emotional disaster; I guess she was just too beautiful for me. I made up my mind that I'd try to avoid getting hurt that deeply in the future. The sure way to get hurt is to take things seriously. I promised myself I'd never let a girl own me."

He has fallen in love again with a lovely girl, Randy Creadick, who is too wise and too feminine to try to own him. It was through Randy that reporters learned of still another secret heartbreak in Micky's life. "Micky doesn't like to talk about himself," she said. "He doesn't want people to feel sorry for him. If it hadn't been for a slip of the tongue I would never had learned that he sometimes suffers great pain. When he was a child he had an illness that might have made him a cripple for life. The illness struck at his bones, and doctors thought he might never walk again. But through prayer and faith in God, he recovered, though he still walks with a slight, almost imperceptible limp. Through the control of mind over the body, he has conquered most of the effects of this illness; it is only when he has to stand for hours at a time that he sometimes feels pain."

The secret heartbreak in Peter Tork's life was a teenage marriage that curdled. "We were far too young to know what love is all about, and we knew even less about how to make our marriage work," he says, wincing with pain at the thought of that youthful marriage.

These are the secret heartbreaks in the lives of the Monkees. When you watch them on your TV screen as characters doing their best to help people in trouble, the image is true to what they are really like. And they're like that because they have suffered.; they know what it is to be hungry and in pain and unhappy.

THE END